Background

A brief introduction to the astronomical concepts and the luni-solar calendar system is helpful to understand some of the terminologies used in explaining the Vedic instrumentation of time and date. The concept of time was long thought of and understood even before geo centric and then later helio centric theories came about.

Human beings have always paid keen attention to the movement of celestial bodies on the sky and took great pains to document those details and consequently were able to rationalize how they would understand the concept of time.

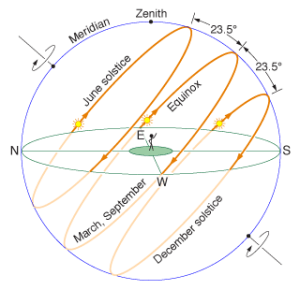

All ancient civilizations did these kind of mappings with the observer as the center of the universe and an imaginary sphere around them which had the paths of celestial bodies. In the Vedic system, passage of “time” was observed with the Sun, Moon, the constellations and the two planets Jupiter and Saturn as constants on the celestial map. For example , the time between one sunrise and the next determined a “solar day” and the time the sun took to traverse through all the zodiac constellations (from Aries to Pisces) determined a solar year. The path of the sun during the year was also observed and mapped. The Sun followed different paths along the ecliptic during the year swaying towards to the northern axis during one half of the year and southwards during the other half of the year. The extremes were at the point where the day was either the longest (summer solstice) or the shortest (winter solstice) with equal day and night right on the equatorial path (for the autumnal and vernal equinoxes).

Similarly, the lunar month was based on the passage of time between a new moon to a full moon and back to a new moon. During such a month , the path of moon was observed to traverse through a set of 27 “nakshatras” or asterisms and this cycle repeated over and over again. (In the vedic calendar, some of the lunar months are named according the asterism that the moon was closest to on a full moon day) Twelve such lunar months were seen to be equivalent to a solar year.

However, the lunar year falls short of a solar year by few days and hence, once in a while a “leap month” (called an “adhika māsa) is introduced to compensate for the offset. It was also observed that Jupiter took 12 years to cycle through the celestial map and return to more or less the same spot whereas Saturn look a longer time of 30 years. And the least common denominator of all these mappings to come to the place where they were all in the same positions was in a span of 60 years.

With all these metrics in consideration, the luni-solar calendar was devised in the Hindu vedic system – called the panchānga (5 limbed/part) which was a reckoning of Solar year, Lunar months, the Nakshtra, Yoga and Karana on any specific day – which determined and predicted first of all astronomical events such as eclipses, sight of comets, etc and became a sort of almanac with previously recorded events which formed the basis for and accurately predicted future events both natural and astrological . This 5 part metric also became the standard tool for determining when certain festivals and rituals related to Vedic practices are celebrated.

One such celebration that is based on a solar (Sauramāna) calendar is the Uttarāyana also used synonymously with the term Makar Sankrānti and celebrated as Lohri, Bihu in many parts of India that follow the solar calendar. Uttarāyana and Sankrānti, however, are terminologies that denote two very different and specific astonomical occurences.

Uttarāyana

Uttarāyana is an astonomical event that denotes the northern movement of the Sun (Uttara = North, Ayana = movement). This corresponds to the six month journey of the sun when its ecliptic is moving towards the north – from the point of winter solstice towards summer solstice, after crossing the vernal equinox.

The days (or daylight period) is on the upward trend as the earth moves closer to the sun on its elliptical orbit.

In this scenario, Sankrānti is when the Sun on its northward sojourn, traverses into the zodiacal constellation of Makara (Capricorn).

Dakshināyana

Dakshināyana, is an astonomical event that denotes the southern movement of the Sun (Dakshina = Southern, ayana = movement). It is the six month period in the calendar year between summer solstice and winter solstice after crossing the (mid)point of autumnal equinox.

The days (or daylight period) is on the downward trend as the earth moves farther away from the sun on its trajectory.

In this scenario, Sankrānti is when the Sun on its southern journey, traverses into the zodiacal constellation of Kataka (Cancer).

This period is generally considered a time of introspection, sādhana and activites that help one turn inward and deliberate. Just as how a farmer plants the seeds for his crops, adds sufficient manure and waters them and cares for them with utmost attention.

Sankrānti

As you may have already deduced, Sankrānti is any point on the celestial mapping where the Sun is observed to cross from one zodiacal constellation to another. There are naturally 12 such sankrāntis corresponding to the traversing of the 12 zodiacs (rāsis) which divide the imaginary celestial sphere into 12 equal parts that correspond to the 12 months).

In the Vedas, each of these 12 positions of the Sun along the ecliptic are represented by a form of the Sun God (Aditya) and hence came to be worshipped as the “Dwadasa-Adityas”

The most celebrated is the “Makar-Sankrānti” when the Sun starts moving in the ecliptic from the constellation of Sagittarius (Dhanur rāsi) to Capricorn (Makara rāsi) during Uttarāyana.

The northern movement of the Sun (after the winter solstice is observed) in combination with its traversing into the zodiac of Capricorn is celebrated for many reasons – for duration of daylight and warmth is on the upward trend, signaling promises of survival for many species on this planet. It sets the stage for receptive energies to get activated at all levels – be it physical, intellectual or philosophical.

This is the time to put into action or reap the rewards of the internal reflection/sādhana that is practiced during the phase of Dakshināyana. Just as the farmer who has patiently cared for his plants all along and will harvest the fruits of his hard labor.

- It is to be noted that Makara Sankrānti will not always signal the beginning of Uttarāyana in the cosmic cycle. We know that the Earth is also wobbling on its axis while it journeys around the Sun and our points of reference change over several milleniums (for example, the north star as we know it today will be a different star). So also will Makara Sankrānti, one day signal Dakshnināyana. The significance of Uttarāyana and Dakshināyana, however, will remain unchanged.

- Other Sankrāntis celebrated are Mesha sankrrānti (Vishu), Karka Sankrānti (Dakshināyana), Thulā sankramanam – though every one of the 12 transitions is observed in some way.